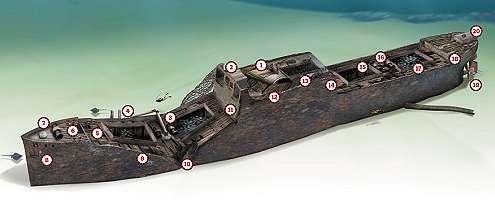

This merchant steamship went down fast from a torpedo strike at the end of WWI, and remains intact off Devon. JOHN LIDDIARD knows his way around it, and so can you. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

IT’S BEEN A WHILE since a Wreck Tour described an intact merchant steamship featuring the classic central superstructure, with holds forward and aft, but this month’s is a nice example of such a ship. The 1,445-ton armed merchantman Lord Stewart was sunk by torpedo on 16 September, 1918, eight miles off the East Devon coast and only a few miles east of the Bretagne (Wreck Tour 21, November 2000).

When I dived the Lord Stewart, the shot had caught in the middle of the superstructure, right next to the remains of the funnel (1), a curved sheet of steel stretching diagonally across a jumble of debris where the upper parts of the superstructure have collapsed.

At the front of the superstructure are the remains of a steel cabin with companionways running either side (2). These are sheltered by raised steel sides of the hull, and the whole structure would have been topped by a wooden bridge and wheelhouse, now long since gone. A trawler had obviously lost its nets over the starboard side of the superstructure, though thankfully I found no signs of monofilament netting.

Moving forward along the starboard side of the holds, the forward mast has fallen to starboard and broken over the side of the ship. By the mast-foot are a pair of cargo-winches (3). The first winch is intact, but the forward of the two is broken apart, with pieces of winch distributed about the deck.

The deck here has fallen slightly into the holds, with ribs from the starboard side of the hull left behind and sticking up slightly (4). Forward of the holds are the usual pairs of mooring bollards (5) on solid steel plates, deck-planking rotting around them.

The forecastle then rises above the main deck, the inside easily accessible through open doorways, or downwards between rotted deck-planking from above (6). Inside it has collected a deep layer of silt, and penetration could be a risky undertaking, even in an easily defined space such as this.

The bow deck is the shallowest point of the wreck at 26m. The anchor-winch is intact (7), with both anchor-chains stretching forward and down through the hawse-pipes. Over the side both anchors are in place, tight against the bows (8). Just a little way back, a pair of small portholes look into the forecastle.

The wreck is covered in anemones and clumps of hydroids, with some particularly fine examples along the tip of the bows. The seabed here is at 34m.

Heading back amidships along the port side (9), the hull dips away much more steeply than on the starboard side. The reason soon becomes apparent. The hull has completely collapsed where the torpedo struck at the bulkhead between the forward holds, the main deck sloping almost level with the seabed (10). With both forward holds flooding, it’s little surprise that the Lord Stewart went down within minutes of being hit.

Back amidships (11) the port side is free of net, leaving a choice of whether to swim along the superstructure or round the outside. Just forward of the collapsed funnel is one of the coal-loading hatches (12), leading down to the bunkers.

Further aft, the engine-room ventilation-hatches have caved in and the area is filled with debris (13). At the port side is the curved skeleton of a shelter above a hatch (14), most likely the main access to the engine-room from above. Like the ventilators, the actual hatchway is blocked by debris.

The Lord Stewart is listed as having two boilers and a three-cylinder steam engine. I spent some time looking for a way down, but could find no obvious way into the engine-room. Judging by the amount of silt in the holds, it could be that the engine-room is also full of the stuff.

The first hold aft (15) is intact, though the wooden decking around it has rotted away in places, allowing light through from above between the steel ribs.

The hold has filled to a couple of metres below the main deck with silt. The Lord Stewart was in ballast on her way from Cherbourg to Barry in South Wales when torpedoed, so there is no cargo to search for and little reason for a diver to disturb the silt.

Between the aft holds are another pair of winches (16). Both are intact, though the mast is completely missing. In good visibility, a look over the port side will reveal it resting on the silt below. The aftmost hold (17) is likewise intact and full of silt.

Short ladders (18) lead up to the stern deck. Rather than proceed straight along the deck, I dipped over the port side and moved underneath to the rudder and propeller (19).

The four-bladed iron propeller is still in place, tips of the uppermost blades home to dense clumps of hydroids, and the remainder of the blades colonised by a mixture of dead men’s fingers and anemones. The tips of the lower two blades are buried in the silt at 36m.

The rudder is covered in purple anemones, and is intact except for a triangular bite missing from the back edge.

Ascending the stern to 26m, a steel box-structure built on the deck is the platform for a 12-pounder gun, officially designated as an “anti-submarine” gun, though it didn’t do the Lord Stewart any good. I suppose such weapons encouraged U-boats to use torpedoes, rather than surface and use their own guns.

The gun itself has been salvaged, though the pintle remains. As with many projecting parts of the wreck, it is covered in hydroids.

GONE IN FOUR MINUTES

With three Royal Navy patrol ships clustered protectively around him, Captain James Hardy of the 1,445-ton armed merchantman Lord Stewart could be forgiven for thinking his ship was safe. So she was – until she reached the west end of Lyme Bay at 8pm on 16 September, 1918, on her way from Cherbourg to Barry in ballast, writes Kendall McDonald.

Five minutes later, a torpedo from UB104 struck the 75m ship on her port side forward and exploded well below the waterline. She started sinking at once, so quickly that the two naval gunners manning her 12-pounder stern gun had no time even to swivel it in the direction from which the torpedo had come. Captain Hardy ordered them to the boats with the rest of the crew.

One of the crew was killed – the sole Spaniard in the crew of 21 was drowned when the Lord Stewart rolled and went down. From the torpedo strike to her disappearance took only four minutes.

One naval patrol vessel dropped four depth-charges on the spot where it thought the U-boat should be, but there was no sign of success. However, no more was ever heard of Oberleutnant Bieber and UB104. He and his crew are said to have been lost when attempting to return to Zeebrugge via the round-Britain route, and struck mines of the Northern Barrage near the Orkneys.

GETTING THERE: From the end of the M5, continue on the A38 towards Plymouth and turn left almost straight away onto the A380 to Torquay and Brixham. After a few miles, turn left again on the B3192 to Teignmouth. On entering Teignmouth, turn left then immediately right downhill to the commercial docks. Turn left behind the dockside warehouses to the public car park. Teign Diving and the public slip are opposite the car park.

DIVING AND AIR: Teign Diving Centre can fill air and nitrox and provide equipment rental and hardboat charter for individuals. Other dive-centres and charter-boats can be found along the East Devon coast from Exmouth to Dartmouth.

ACCOMMODATION: B&B at the New Quay Inn, Teignmouth.

TIDES: Slack is between 2 hours and 1 hour before high water or low water Plymouth.

LAUNCHING: The slip at Teignmouth is usable at all states of the tide except very low springs. Other slips are available at most ports along the East Devon coastline.

HOW TO FIND IT: The GPS co-ordinates are 50 29.610N, 3 16.990W (degrees, minutes and decimals).

QUALIFICATIONS: Suitable for experienced sports divers, with nitrox being a big advantage in this depth range.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 3315, Berry Head To Bill Of Portland. Ordnance Survey Map 192, Exeter And Sidmouth. World War One Channel Wrecks, by Neil Maw. Dive South Devon, by Kendall McDonald. Shipwreck Index Of The British Isles Vol 1, by Richard & Bridget Larn.

PROS: An excellent example of a classic merchant ship of the era.

CONS: Visibility can be low, especially after heavy rainfall.

Thanks to Mark Layton, Andy Wallace and also to many regular divers with the Teign Diving Centre.

Appeared in Diver, December 2001