When WW2 ended 70 years ago, an adapted gas-control regulator hit the market and recreational scuba got the boost it needed. And old-school twin-hose diving isn't dead yet – vintage kit and training has much to commend it, says STEVE WARREN.

MIKE WARREN HAD BEEN DIVING, but on boarding his boat he found that he had fouled his anchor. With little air left, he re-entered the water to retrieve it.

Mike was using double cylinders with a decades-old twin-hose regulator and a back-up regular single hose. He switched to this for the anchor recovery because it breathed more easily at low tank pressures than the twin-hose.

“I became aware of a loud noise in the background, much like a boat engine and quite close. It was very annoying,” Mike explained. “Then the noise stopped abruptly, and so did my air.”

Grabbing the anchor, which he had that moment dislodged, he casually made a 15m free ascent back to his inflatable. “The twin-hose had floated over my head and gone into freeflow, causing all the racket and emptying my tanks…” Diving with vintage scuba equipment has its moments. Mike had just survived one.

When I was growing up in the 1970s, divers on any beach drew a crowd. To be a scuba-diver was to be an explorer. I was a keen snorkeller, but my age counted against me when it came to joining the ranks of the aqualungers. I could only look on.

Now diving is open to all-comers but the early sense of adventuring is long-lost. Andrew (AJ) Pugsley and I were intrigued by a period on which we had missed out.

Vintage regulators and learning the techniques that went with them we saw as a link to those halcyon days. Mike, a Brit based in Antibes (and not a relative) was our mentor.

EARLY RECORDS indicate many failed attempts to invent equipment to allow humans to remain under water beyond the measly limits of a single breath.

Unrealised aspirations dating back to the 1600s included scuba tanks, regulators and even rebreathers, all frustrated by the limited knowledge and crude technology of the time.

It was surface-supplied equipment that won out. An unlimited air supply from above meant that mechanically simple freeflow systems worked well below. All that was needed was a hand pump and men to work it.

Though hoses limited divers’ mobility, for a salvor or shellfish-farmer being able to range far and wide was not a priority. To make recreational, exploratory diving a reality, a way to disconnect from the surface and roam freely with divers carrying their own air supply was needed.

And we nearly got that in 1864, a full 102 years before PADI existed.

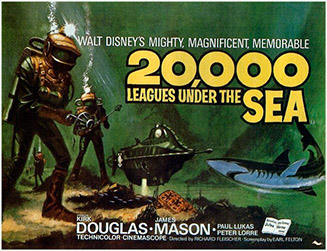

The Rouquayrol-Denayrouze diving apparatus incorporated both an air tank and a regulator. It featured in the 1870 novel 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea as Captain Nemo’s hunter-gatherers stalked through Jules Verne’s richly drawn undersea forests.

But it was also artistic licence, because the cylinder was pressurised only to 30 bar.

The R-D diving apparatus remained tethered to the surface by a hose, with the cylinder relegated to a bail-out. Until the last century metal cylinders could not hold enough pressure to create an air supply with sufficient duration to be practical for working dives.

Even today, commercial divers rely primarily on surface-supplied gases for much this reason. At 120m, a 12-litre cylinder provides fewer than 50 breaths – only enough for the diver to return to the safety of the bell if the surface supply fails.

Motorised compressors have replaced hand pumps and lightweight helmets have superseded the copper helmet of yore, but the similarities of modern surface-supplied diving outweigh the differences.

SPORT SCUBA-DIVING has its origins in 1920s France. Yves Le Prieur combined a small air tank with a freeflow valve that enabled the brave and the curious to venture under water.

In 1936 the first recreational scuba-diving club was founded in Paris. But the freeflow system was wasteful of the limited air supply so excursions were brief. The freeflow problem still needed solving.

Various inventors tried their hand at improving on the R-D concept, which supplied air only when the diver needed it.

In 1943, with France under Nazi occupation, Jacques Cousteau and Emile Gagnan came up with a successor to the R-D regulator.

The diver breathed normal air from a tank through a series of levers, diaphragms and springs routed through two hoses – one took air to the diver, the other took his exhalations away and vented them.

It supplied air only while the diver was breathing in. The flow stopped instantly when the diver stopped inhaling, using the diver’s own lungs as the on/off switch.

With none of the precious air supply wasted, exploration time and depth limits were suddenly greatly extended.

At the end of the war the industrial gas giant Air Liquide put into production the Cousteau-Gagnan regulator – the CG45. The seeds of Le Prieur’s sport-diving movement were now shoots.

The CG45 was derived from a valve developed for running cars on gas. Early sport divers unwilling to pay for “proper” regulators would often take the same route, using gas-control components to create “Calor Gas” regulators.

The CG45 dropped air pressure in two stages, as do today’s single-hose regulators, but in 1955 manufacturer Spirotechnique (spun off from Air Liquide and known today as Aqua Lung) replaced it with the simpler Mistral, a single-stage regulator that reduced tank pressure to ambient in one jump.

Take a 60-year-old Aqua Lung Mistral apart and the economy of engineering is striking: a large diaphragm that collapses onto two levers that open a spring-loaded valve to admit air from the tank, which flows to the mouthpiece through one hose, and another hose that leads exhaust air to a simple flap-valve called a duck’s bill that releases it into the water.

With simplicity comes reliability, and rare problems are quickly rectified.

“You could often strip Mistrals down and sort them out while on a dive-trip,” says Colin Doeg. If Mike was our mentor, Colin was our inspiration. He co-founded, with the late Peter Scoones, the British Society of Underwater Photographers.

Its elder statesman fondly recalls twin-hose demand valves, or DVs, as regulators were known in the UK: “Long ago, learning how to use the things was a rite of passage for everyone who joined the British Sub-Aqua Club,” he says.

“The tubes carrying the air from the demand valve to your mouthpiece used to fill with water. You had to learn to roll over onto one side – I can’t remember which one – pinch that tube so the chlorine-rich water gathered on that side, and then blow hard to get rid of it.

“Then came the big breakthrough – non-return valves. They stopped the water getting into the tubes from the mouth-piece.” Colin scowls: “They were much harder to breathe from than single-hose demand valves.”

Single-hose regulators place the second-stage diaphragm in the mouthpiece. It’s the mechanism by which incoming tank pressure, already reduced once by the cylinder-mounted first stage, is finally reduced to a breathable pressure.

The location of the second-stage diaphragm is key to a modern regulator’s ease of breathing in almost any attitude.

A twin-hose has its diaphragm mounted on the tank, and breathing effort depends on getting its positioning perfect. It needs to sit between your shoulder blades.

The first time I used a friend’s twin hose, I loved it. The second time I used the same valve, I felt I could barely draw breath. My mistake had been to let my tank ride high, raising the regulator mechanism.

It was sensing a lower hydrostatic pressure than my lungs were, and I had to pull air from the valve.

It was as if the air had morphed into a McDonalds shake, the hoses into straws.

EARLY SCUBA HARNESSES use a jock-strap to keep the tank low and the regulator properly positioned.

The Spirotechnique Dumas tank harnesses (named for Cousteau’s team-mate and co-author of The Silent World) that we use have only shoulder-straps mounted high on the cylinder neck and a crotch-strap.

A waist-strap isn’t needed because the Spiro weightbelt buckle is notched to take the jock-strap.

The old rule that the weightbelt went on last ensured that it lay over the jock-strap. In an emergency the weights could be ditched without tangling in it. The Dumas harness is refreshingly uncomplicated and surprisingly comfortable.

Misunderstanding the importance of proper positioning was one of the factors that drew undeserved criticism of the Aqua Lung Mistral twin-hose regulator introduced in 2005, a half century after the original.

Admittedly it didn’t help that the design of some of Aqua Lung’s own BCs meant that you couldn’t lower it enough in the backpack to optimise performance.

Twin-hose regulators had been quickly rendered obsolete by single-hose models and largely vanished by the early 1970s. Before the Aqua Lung Mistral, the last production twin-hose, the Spanish Nemrod Snark 111, had disappeared with Nemrod itself in the late 1990s.

Single-hose regulators offered much easier breathing, had take-offs for direct feeds and a realistic expectation of supporting a diver sharing from an octopus rig in recreational depths.

The Aqua Lung Mistral was adapted from an existing single-hose first stage that incorporated all these advantages, but why make a “modern” twin-hose, and who would want one?

Smartly, Aqua Lung played the nostalgia card and released a special collector’s edition, which sold well to the trade. But there’s more to wanting an updated twin-hose than nostalgia, hoping to stand out on the dive-boat or as an investment.

THE BIG ADVANTAGE with twin-hose regulators is that bubbles are exhausted behind your head, and for underwater photographers and cameramen this brings two significant benefits.

Firstly, your exhalations don’t get between you and your viewfinder or monitor. Shooting video, it’s frustrating to tilt your camera upwards and have your bubbles run into your monitor hood and obliterate your view of the action or end up in shot.

If filming for TV I use radiophones, and had been forced to use single-hose regulators and accept this problem.

Now I’ve found a mic’ed up full-face mask that will work with comms and my Aqua Lung Mistral. Problem solved.

Colin explains the second benefit: “Twin-hoses were one of the best accessories an underwater photographer could have. Your body shielded the noisy exhalation of the bubbles, making it much easier to approach timid creatures than if you were using a single-hose demand valve. That was why I bought my Royal Mistral – I’d finally worked out why one of my friends could get so near to fish without spooking them.”

Professional underwater cameramen and photographers such as shark specialists Dan Beecham and Tom Peschak own Mistrals for these reasons. Tom also thinks they can be safer around sharks because of the clearer field of view.

Rebreathers also overcome these issues, but they are more complicated and require support not always available on location.

Military divers, including US Navy SEALs, begin their rebreather training on twin-hose regulators. Aqua Lung’s military division built the Mentor, a conventional twin-hose, more like a CG45 than its Mistral, for these users.

The original Aqua Lung Mistral was hugely successful and made under licence in Britain by Siebe-Gorman, pioneer of the closed-dress diving helmet. Mistrals were also built by Spirotechnique’s North American subsidary US Divers.

Cousteau incorporated the improved Royal Mistrals, with the addition of non-return valves, into the sleek yellow scuba-sets built for his first major TV series in the late 1960s, the show that did so much to popularise recreational diving.

Colin praises the aesthetics of twin-hoses: “They produced much better photographs of divers because the bubbles were exhaled from behind the body rather than splurged out all over the face, and the chandeliers of bubbles marching up towards the surface were exquisite, especially if they caught the sun.”

LONG AFTER SINGLE-HOSE regulators took over in recreational circles, twin-hose remained the first choice for polar exploration.

Damien Sanders, Field Diving Officer, BAS (British Antarctic Survey) South Georgia and Signy Island 1979-1982, explains why: “BAS used single-stage Spirotechnique Mistrals into the mid-1980s, for several reasons – they worked and were simple.”

“Twin-hose regulator mechanisms were inherently less prone to freezing because of the large diaphragm casing and because the mechanism inside remained dry.”

“They were not infallible, however. Twin-stage regulators, whether single- or twin-hose, had more parts, and took more skill and specialised equipment to service and set up. Many BAS divers were not very experienced, nor trained technicians.”

“Back then BAS, like many organisations in Britain, were very professional about being amateur, raising muddling-through to an art form. They disliked seeking outside advice, and a whole mythology grew up as to what was and was not possible.”

“By the mid-’80s the regulator parts were becoming unobtainable, cylinder pressures rose, making a single stage almost impossible to adjust so that it could function effectively over the whole pressure range, and Health & Safety and formal training and qualifications also reached the seventh continent.”

Air management was a concern for early scuba-divers. Cousteau favoured reserves, rather than pressure gauges. His earliest sets and, later, some of the fairings used on the TV shows, used banks of three or four cylinders manifolded together.

One of the cylinders was linked to the others by an isolator valve. When the air ran low in the main cylinders, the diver opened the isolator and used the last tank for the ascent.

More popular with sport-divers were reserve valves built into the tank-valve or regulator first stage. Our own vintage cylinder sets use these. They hold back 30-50 bar, and when this pressure is reached, breathing starts to tighten.

A spring-loaded mechanism in the tank-valve closes off the air supply and pulling a rod stowed beside your cylinder retracts the restrictor and lets you breathe your remaining air normally.

The reserve provides a physical warning that you’re getting low on air.

With twin cylinders only one tank is used to hold back the reserve air supply. When you open the valve it flows into the other cylinder to achieve equal tank pressures and a nearby buddy can hear the whine, and is alerted that you’ve pulled and need to ascend.

Reserves were superseded by pressure gauges, which allow for more precise air-management, but divers run out of air because they don’t look at gauges as often as they should. When I started diving I used both a reserve and a pressure gauge, a nice belt-and-braces system.

Even so, we made one dive on which the reserves could have got us into trouble. Mark Koekemoer, AJ and I were diving using Mike’s sets. Each cylinder had a reserve, which we all checked visually was primed. None of us had pressure gauges.

We had a great dive, but no one pulled their reserve before it ended. Then Mike shared something he hadn’t thought to mention earlier: “Don’t trust the reserves. I had to cobble the tanks together and the pull-rods aren’t the right ones. They’re just a little bit short, so the reserves won’t operate. They’re already open. Anyway, don’t worry about it now.”

In fact, if you breathe gently enough, you can actually draw air past some reserves, as Colin recalls: “My tank had a reserve incorporated in the tap, so it was easier to concentrate on the picture you were trying to take.

“That left only one snag – if you were concentrating on what you saw in the viewfinder you could easily miss the suck-a-bit-harder warning, and you never realised there was a problem until you reached the second stage – no more air!”

Release a twin-hose and the natural buoyancy of the hoses causes the mouthpiece to float overhead, where it free-flows mercilessly, as Mike discovered. Divers learned to perform backward rolls to recover a lost mouthpiece quickly.

As a BSAC instructor in the 1980s I still taught this skill, though twin-hoses were already lost to history, and without knowing the reason. It was fun and reaffirmed the quirks of weightlessness and the joy of becoming an instant gymnast. PADI disallowed such frivolity.

Some attempts were made to build octopus-rigs onto twin-hose regulators, but safe seconds came of age some time after single-hose regulators took over.

Even then, as today, there were concerns about tank-valves and first stages supplying enough air to support two exerting divers at depth with little air left.

Veteran divers mostly learned to buddy-breathe, a practice largely banned from training now. It involves passing the mouthpiece back and forth between the donor and the out-of-air diver.

With a twin-hose the technique seems to be a variation on the knee-trembler. Dennis Santos, a former BSAC Diving Officer and Navy Reservist diver with more than 40 years’ experience, explains: “When you needed to share you had to ensure that the donor was below the recipient. You link up and the guy needing air gets slightly above you.

“As you pass up the mouthpiece, the regulator goes into freeflow, clearing itself of water. If not, the recipient would have had to blow to clear the mouthpiece before taking the first breath.

“After two breaths, it’s your turn and you shimmy up a little so the regulator is now passed up to you. You repeat this all the way to the surface.”

BOYS BEING BOYS, some of our vintage dives have taken place off a small French beach at night, without torches, as we had none, and no shorts either. Mark and I were on scuba when AJ snorkelled down to see if buddy-breathing worked. It does.

There is strong interest in diving vintage kit, and groups such as the Historical Diving Society provide the hub.

We began by diving privately from the shore. We were concerned that the threat of liability might prevent us using the equipment on supervised dive trips, but we’ve found diving professionals to be surprisingly open-minded.

AJ remembers being let loose in the Maldives: “The liveaboard’s senior divemaster had stepped away as we were setting up kit for our final dive of our trip. I wanted to dive my Mistral, but as it’s not really a current item I thought it polite to check with her first – I went ahead and rigged my tank for old-school diving, hoping she’d be fine with it (sometimes it's easier to take the reprimand than to get permission first).

“That meant harness-only and twin-hose regulator with a weight-belt correctly set up. The other divers started with the jokes about diving on the boat’s plumbing system, then observed that the regulator was about twice as old as me (I was 22) and bore none of the modern refinements of their regs. After a quick look the divemaster approved our plan and we had a wonderful dive, though with a sense of bewilderment among the others.”

Along with modern Aqua Lung Mistrals, AJ and I own and dive four different classic Mistrals from Spirotechnique, US Divers and Siebe-Gorman alongside lesser-known brands.

Collectors rank twin-hose regulators by age, labelling, whether or not they have take-offs for pressure gauges and even shape. The earliest CG45s are rectangular, later models round.

Howard Ryan is another collector and user of vintage twin-hoses, brought up on 1960s TV adventure shows such as Barrier Reef and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, which feature twin-hose regulators.

“I have a childhood memory of trying to build a ‘twin-set’ out of two empty bottles of washing-up liquid and a couple of bits of flexible tubing – sadly it didn’t pass its initial bath-time test,” Howard recalls.

“Today I own a US Divers Royal Aqua-Master and I’ve also got a British Submarine Products Black Prince, which sounds suspiciously like something that might be bought from Ann Summers.”

But it isn’t just kidults trying to reconnect to history who want twin-hoses. Sometimes those who made history also desire them.

CG45s are rare and can fetch thousands of pounds. Mike, a collector, had several. A buyer was referred to him, and on meeting Mike immediately offered him one of his treasured CG45s for free. It was Albert Falco, former chief diver of Cousteau’s Calypso.

Falco declined the CG45 as an outright gift. Instead he exchanged the Omega Seamaster watch he had worn during his famous dives to the shipwreck Britannic.

“A good man must have a good watch,” Cousteau had once told Falco, passing him one of his own. Now Falco extended that tradition to Mike.

THE EQUIPMENT IS AGEING, and many original components are perishable rubber. Those who used to service regulators are long retired if not departed. But surviving veterans have pooled information and shared resources to keep the regulators going strong.

In the USA replacement parts such as diaphragms and hoses are being made from modern synthetics. Special adapters, converted from regular single-hose first stages, enable today’s direct feeds and safe seconds to be coupled with ancient twin-hoses.

A new twin-hose, much more akin to traditional models than the Aqua Lung Mistral, has been built through crowd-funding. The philosophy behind the Argonaut Kraken parallels the individuals who created diving marques from kit lovingly hand-crafted in garages and on kitchen tables back in the day.

The Cressi brothers, Ludovic Mares and George Beuchat sired some of the proudest of contemporary brands, while Italian WW2 Special Forces frogman Luigi Ferraro founded Technisub, which continues as part of the Aqua Lung group.

ONE OF OUR LAST DIVES off Antibes we held a twin-hose rally – more of a costume party, really. Six of us descended to play in the seagrass meadows that might once have inspired Verne and entertained Le Prieur’s underwater ramblers.

AJ ditched his set, surfaced and dived to refit it. It was a risky strategy as he wasn’t sure he could get back to his cylinder.

Ditch-and-don used to be part of scuba-training, a confidence-builder. It reminded me that Dennis went shares on a scuba set in the 1960s. Wearing sweaters for what little imagined warmth they offered, he and his buddy would swap the tank on the seabed at the halfway point.

To dive with the old equipment, in the old ways, is liberating. There is so much modern equipment encumbering today’s diver that adds drag and demands attention that it distracts us from the intimate pleasures of being under water.

To explore without BC, pressure gauge and a Bat-belt of accessories is a joy.

It can seem that we’re a little cavalier in diving vintage kit and adopting practices abandoned a long time ago. In this age, hopefully temporary, of heavy-handed diving controls and cowed by liability, we risk making our recreation a trial.

But we’re good divers fooling around and doing what we got into diving to do. Having fun.