WRECK DIVER

Volunteers divers have been beavering away around the UK coast since 2014, recording wrecks such as the doomed War Knight and helping to bring their stories back to life. JESSE RANSLEY reports on their mission

OVER THE PAST FOUR YEARS, archaeologists and volunteers from the Maritime Archaeology Trust (MAT) have spent 257 hours (or, to be precise, 15,423 minutes) under water, diving World War One shipwrecks off England’s South Coast.

Between 2014 and 2018 they have photographed, surveyed and investigated 36 sites. They have also been researching the shipwrecks in historical archives and record offices across the South.

All this work has pieced together the stories of these wrecks, along with those of more than 1000 other South Coast WW1 sites, for the “Forgotten Wrecks

of the First World War” project. Funded by the Heritage Lottery to coincide with the centenary of the war, the project investigates a vital but largely forgotten struggle that took place daily.

“Everything necessary for the war, from troops and munitions to food, materials and intelligence, moved by sea,” says Julie Satchell, MAT’s Head of Research. “But beyond the big naval battles, the war at sea has been largely forgotten.

“The thousands of WW1 shipwrecks in UK waters offer a unique insight into the war, but they are increasingly fragile and haven’t been recorded.

“Through the project, we’ve been able to investigate some of these wrecks on the seabed and connect that work with their stories from the archives – and, in some cases. to the stories passed down in the families of survivors.”

Volunteer-divers were crucial to the project. “It wouldn’t have been possible without their work or the support of dive-clubs from the South Coast,” says Satchell. “One of the project’s key aims was to work with the dive community and to provide information and resources to enhance their wreck-diving experiences, but we’ve also learnt so much from local divers – all their experience and knowledge is invaluable.”

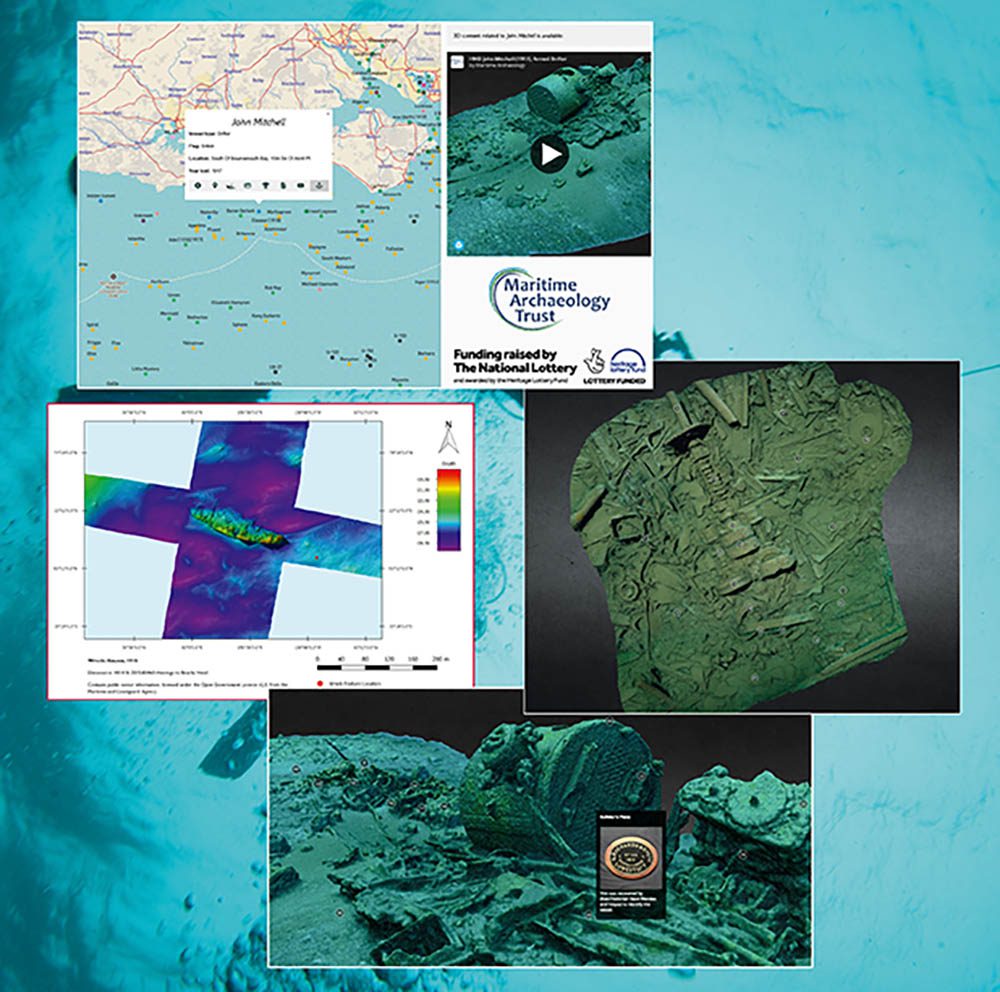

The project’s new online, interactive wreck map offers a unique resource for recreational diving in the UK.

It connects the results of all that research to the wreck-sites, so that anyone can click on a wreck and access underwater images, videos, 3D site models and geophysical images, as well as stories of the ship’s loss, historical documents, archaeological site reports and, in some cases, images of artefacts from the wrecks.

“We’ve had an overwhelmingly positive response,” Satchell reports. “We’ve heard from divers and clubs all over the country and abroad. It’s been online only for a couple of months, so we’re really keen to hear how it’s used by divers in the coming year, but it’s certainly offering inspiration to divers to explore some less well-known wreck sites – we’ve already heard from clubs who’ve started using the map to plan dive-trips.”

One of the first wreck-sites dived during the project was that of ss War Knight. The ship, which lies at a depth of about 13m in Watcombe Bay, Isle of Wight, was lost in dramatic circumstances, but the story faded after the war…

Also read: Exploring Baltic Shipwrecks in Sweden

WAR KNIGHT

War Knight was a US armed cargo ship, heading to London as part of a large convoy in 1918. In the early hours of 24 March, the convoy took defensive measures, running without lights and then altering course twice.

In the darkness War Knight collided with the OB Jennings, a huge tanker carrying a highly flammable gas. Fires broke out on both ships and across the sea surface.

War Knight was towed, ablaze, towards shallow water but hit a mine. She was eventually sunk by British gunfire in Watcombe Bay to extinguish the flames.

Little on the seabed suggests the dramatic nature of the wreck’s sinking or connects it to the remarkable film footage from the archives of the Imperial War Museum of the ship ablaze.

It’s the sort of site that many divers would pass over, with only the steam turbine standing proud of the seabed. But for one of the team’s 17 volunteer-divers, War Knight stood out.

Andy Williams has an engineering background and, after the diving was complete, he began researching the engine, “a very early example of a marine steam turbine being used in a commercial ship”.

The data and photographs from the dives were pieced together into a photogrammetry site-plan, along with a 3D model of the steam-turbine engine. Williams says his work on the project gave his diving “a sense of purpose”.

He has given lectures to engineering societies since, using the images and 3D models and, as he explains, “it’s fascinating to be able to present such a remarkable image to people who were working on steamships not very long ago, who see things in the images that no diver would ever pick up”.

ALAUNIA

Unlike War Knight, no diver could pass over the wreck of ss Alaunia by mistake. The 165m Cunard passenger liner, one of the largest wrecks in the UK, lies off the East Sussex coast. At between 24 and 36m, with the bow particularly well preserved and rising to 12m off the seabed, it’s a popular dive-site.

Alaunia sailed routes from North America to the UK, and was requisitioned as a troopship during the war. She was the first Cunard ship to transport Canadian troops to Europe and, in 1915, was involved in transport for the Gallipoli campaign.

In addition to troop transport, Alaunia continued commercial trips and was on route from New York, unarmed, when she struck a mine on 19 October, 1916. Two of the 165 crew died (including the 16-year-old trimmer, who was working in the engine-room).

HMD JOHN MITCHELL

In contrast, probably only a dozen people have dived HMD John Mitchell. It was just the kind of small ship that is often left out of the story of WW1.

Like other fishing drifters built for managing huge drift-nets in heavy weather, she was readily adapted to war duties. In 1915 the John Mitchell was armed and deployed as a “net vessel”, patrolling anti-submarine nets.

The wreck now lies 15 miles off Swanage, Dorset at 40m, having collided with ss Bjerka in November, 1917. The ship had been one of at least 40 steam drifters hired by the Admiralty and lost off the South Coast alone.

The wreck is fairly intact, though much of the wooden planking on the starboard side is gone.

Thanks to some amazing visibility, the project team were able to measure, video and take thousands of photos as part of a photogrammetry survey, and then pieced it together to produce a full virtual-reality 3D tour of the John Mitchell.

GALLIA

A few miles south-west of the John Mitchell, the wreck of the large steamship ss Gallia lies on its port side in 38-40m about 11 miles off Anvil Point on the Dorset coast.

With parts of the wreck, including hull-plating, still intact, it’s a fascinating wreck-dive, but its identity had never been confirmed.

Gallia was an Italian collier steaming from the Tyne to Savonia in Italy in 1917. Without warning, on the afternoon of 24 October, it was torpedoed by German submarine UB40.

The torpedo struck on the port side, penetrating the engine-room, and the ship sank fast. All but one of the 27 Italian crew were rescued, though two died soon afterwards.

When the MAT team dived the site in June, 2015, they had exceptional visibility in excess of 30m. Again the team surveyed and recorded the site and produced a 3D model. With the images and model, combined with historical research, MAT confirmed the wreck’s identity.

THE STORIES OF THESE four wrecks, though extraordinary, were also everyday during the war. Germany was intent on squeezing Britain’s military supply lines, but also on targeting its merchant and transport shipping.

The 1100-plus wrecks in the project area reflect the scale and breadth of the vessels lost during the conflict. They include ocean-liners, cargo-ships, fishing-trawlers, submarines, troop-carriers and hospital ships – naval and commercial, steam and sail.

Perhaps surprisingly, 66% of the wrecks were merchant vessels and 9% fishing-boats, compared to 8% military and 4% on mine-sweeping duties.

Similarly, many of the ships, such as the Gallia, were not British but from all over the world (10% were Norwegian, 6% German and 7% French).

Everyone has a story worth telling. Robert Morgan, one of the volunteer-divers on the trust’s team, had never been involved in archaeological diving before, and found that the project reminded him “of the history and value of the sites we dive… I think that divers sometimes need reminding that wrecks aren’t just tangled messes of rusting metal on the seabed; they tell an otherwise-forgotten story of individuals and societies that most people aren’t lucky enough to see or feel.

“Once you know the stories of these wrecks, it’s very hard to see them as just metal and wood on the seabed. It changes the way you see – and dive – them.”

In August, 2018, skipper Dave Wendes and members of the MAT team returned to the site of ss War Knight – this time with two relatives of the men who died as a result of the collision, to lay poppies above the wreck.

Remembrance and commemoration are key to the project, through uncovering stories and connecting people’s lives to these wrecks, through exhibitions, articles and videos, but also through the experiences of the divers.

Many of the volunteers, even the experienced divers, found the project changed the way they approached wreck-dives.

“As a cameraman, it’s easy to be detached from the realities of what happened,” explains Mike Pitts. “I stay focused on the dive, my depth, my remaining air and how best to film in a relatively short window of time, but on the ascent, when I leave the wreckage behind, I look back down and think of the souls that are still there.

“On land-based equivalent sites it’s rare to see the aftermath of war like this. But here, the First World War is open to those that make the journey.”

MAT is hoping that all the research and resources available through the wreck map will enable other divers to make that journey. The four wrecks mentioned here are just a snapshot of the 1100-plus sites in the map, which you can find on the Forgotten Wrecks project website

There are so many more stories and possible dives just a few clicks away. If you’re interested in diving with MAT on future projects, becoming a friend of the trust or checking out its other projects, more information can be found at MARITIME ARCHAEOLOGY TRUST