The deep site of a Roman shipwreck was found near Crete well over a century ago. Among other artefacts it yielded the world’s oldest-known computer.

Cousteau, inevitably, was there, but only recently have divers brought modern technology into play, reports team-member ALEXANDROS SOTIRIOU. Photos by ALEXANDROS TOURTAS

YOU’RE DRIFTING off your intended course in uncharted seas during a storm. Your vessel is a timber sailing ship, with no engine or electronic equipment, and it is heavily laden with precious works of art.

The waves keep torturing the ship, and every man on board is kept busy battling to control the rising level of water in the holds.

The brutal sound of waves smashing on nearby rocks gives you hope for your own salvation, as the ship will soon be going down.

This is how it must have felt to be aboard the Roman ship that sank off Antikythera Island, about 20 nautical miles north-west of Crete in the Aegean Sea, in around 60-50 BC.

“The vessel was most probably one of the largest of her time, believed to be more than 40m long and at least 14m wide, with a minimum hull depth of 6.5m and a cargo-carrying capacity of 2.3 to 2.5 tons,” says Aggeliki Simosi, the head of the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities (EUA), and director of Antikythera Project 2012.

The vessel had probably been chartered by a wealthy merchant to transport a selection of works of art.

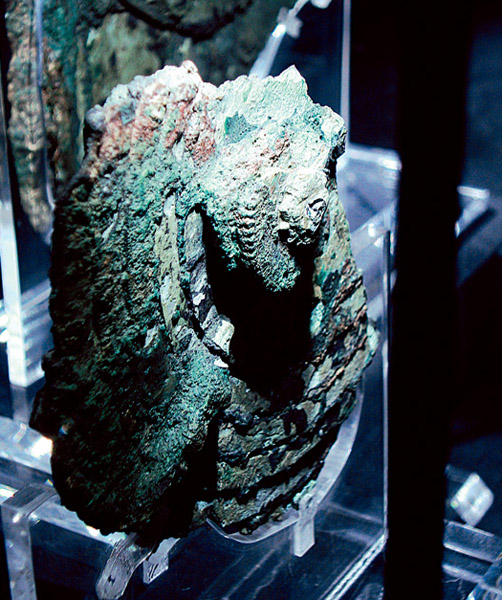

The cargo included bronze and marble statues but also various other unusual artefacts, such as the Mechanism of Antikythera, now recognised as the world’s first-known “computer”.

This was a complex instrument that could calculate the position of certain stars and planets, and was also capable of predicting eclipses of sun and moon.

Antikythera is a fairly small island (6.5 miles long, two miles wide) strategically located on a busy sea trade route connecting eastern and western Mediterranean coasts.

It has been inhabited since Antiquity, and thrived until World War Two, when some 800 Antikytherans were evacuated to Crete by German occupation forces.

Today, fewer than 30 people live on the island, which is connected to the rest of Greece only three times per week through its ferry service.

Its store is also the cafe, taverna and post office. There is no public transport, healthcare facilities are basic, and time runs really slowly.

AROUND EASTER 1900, a small sailing boat carrying a group of Greek hardhat sponge-divers found shelter on the Antikythera coast during a storm. One of them kitted up to collect seafood for the crew.

The rocky cliffs dropped almost vertically from high above the sea to deeper than 40m. With visibility of at least 30m, the diver could see the bottom long before he reached it, but could hardy believe his eyes.

Petrified human and animal figures were scattered everywhere on the seabed below him. Fighting warriors, dancing women, running horses – all were partly buried in the sand.

He thought nitrogen narcosis might be playing tricks with his mind. Grabbing one of the arms that extended from the sand, he signalled the tender to ascend. The crew would never believe his story without proof.

The sponge-divers soon returned with enough equipment and support to conduct the first known underwater archaeological salvage for the Greek government.

Works started in 1901 and lasted for almost two years. The 2000-year-old time capsule had been opened, bringing valuable information and artefacts back to light.

Work conditions were extreme, and often dangerous. With diving depths down to 70m, the divers were able to spend very little time on the bottom, but still ran a high risk of decompression sickness. Not all of them made it back safely, and some even died.

The work became increasingly demanding as the findings became fewer. It was decided to abandon the works at the point when no important remains were left on the bottom.

Famous finds included the Mechanism of Antikythera, the Youth and the Philosopher statues, parts of other bronzes, 36 marble statues and a number of other artefacts.

More than 70 years later, Jacques Cousteau and his team visited the ancient shipwreck to film a documentary.

Technological advances since the previous expedition meant that within a few days the divers had managed to further enrich the collection of artefacts, now housed at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

IN OCTOBER LAST YEAR, an international team of Greek, American and British archaeologists and divers visited Antikythera once again.

The objectives of Project Antikythera 2012 were to survey the entire underwater coastline to depths of 40m, relocate the shipwreck site and conduct a full underwater archaeology project.

Every operation would be carefully documented to produce a digital database with detailed reports, stills and video.

State of the art closed-circuit rebreathers, diver propulsion vehicles and high-definition cameras were available, along with technological and financial support from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

Team-members spent a week in Heraklion on Crete, refreshing their diving skills and checking equipment and procedures. Local dive-centre owner Dimitris Drakos would provide support, including boats.

THE FIRST TASK on arriving in Antikythera was to set up our shore base. A modern hotel overlooking the harbour, with 12 guest-rooms and a fully equipped kitchen, provided everything we needed. We had sourced provisions for a 20-day stay.

The 10m dive-boat and a 7m support RIB were brought to the port and a filling station was set up. Sufficient oxygen and helium, two fuel-run compressors and a gas-driven booster pump were put in place.

First-aid equipment and helicopter evacuation arrangements formed part of a detailed emergency plan, with remaining details finalized on the spot.

Underwater archaeologists Dr Theotokis Theodhoulou from EUA, Dr Brendan Foley and Alex Tourtas from WHOI, were very systematic.

The underwater terrain is rocky and highly anomalous, making it impossible to distinguish between man-made and natural objects on the seabed using acoustic bottom survey equipment.

Also, the numerous rocks extending up to 20m above the surrounding seabed could present a serious hazard to towed underwater oceanographic equipment.

Divers able to manage extra-long underwater times and comfortably cover long distances had to survey the bottom visually, helped by the CCRs and DPVs.

Diving was mostly based on VGM algorithm multi-level no-decompression profiles, starting from 40m and ascending by 5m every time the no-deco limit was down to two minutes.

WITH 90-MINUTE bottom times and three overlapping teams, the first task was accomplished in just eight working days – covering 22 miles of coastline.

EUA divers Manolis Tzefronis and Louis Mercenier manned the safety boat, following progress via an SMB signalling protocol. Various points of interest were noted for future operations.

We had a rough idea of the position of the shipwreck based on notes and descriptions from previous operations, but no fixed position.

I and British technical diver Phil Short surveyed a wide area down to 65m using trimix, keeping to maximum decompression times of 30 minutes.

It helped in understanding and remembering the topography of the bottom that we could take narcosis out of the equation.

Ancient shipwreck debris could be recognized even when scooting over the bottom at high speed.

Scattered pieces of pottery led us to the cargo. Amphorae characteristic of the wreck had been studied by the team in the dedicated exhibition at Athens’ National Archaeological Museum, and the divers were certain when they sent up an SMB bearing the note “found the wreck” that the famous Antikythera Shipwreck site had been relocated.

The cargo and certain decay-resistant parts made of lead, bronze and so on is all that can be seen on the seabed. Timber remains are likely to be found only if buried under the sand.

The advantage of modern diving techniques is that you can stay safely for 30-40 minutes at depths where divers on previous expeditions could have spent no more than 5-10 minutes.

As a result we were able to document all the visible parts of the cargo and wreck.

The site dimensions were carefully measured by Alex Tourtas. Artefacts scattered across a 60 x 20m surface indicated one of the biggest ancient cargos ever found. Ed O’Brien, WHOI diving safety officer and expedition team diver, described the ship, based on its size, as the “Titanic of its time”.

Cargo samples were raised to help in positively identifying the wreck. A lead anchor part was also located and raised.

Calcium deposits on the surface of some artefacts had concreted them to the surrounding rock. It took two days’ work to free them gently before raising them.

SALVAGED ITEMS underwent initial on-site conservation (mechanical cleaning and desalination) before being sent to EUA labs for further care.

With only four bad-weather days over the four-week project period, only minor equipment failures and no other serious drawbacks, luck was on our side.

The Antikythera Project 2012 yielded important results in documenting this site, and demonstrated the value of using CCRs with DPVs to survey a whole island for scientific purposes. The combination was proven effective, safe and relatively comfortable.

DIVING ANCIENT WRECKS

Want to visit a 2000-year-old Greek wreck site? There are still heavy restrictions at present, but this could become possible a few years down the line.

Only scientific institutions working under a special license are currently allowed to work on underwater antiquities in Greece. Sport-diving cannot take place on sites of archaeological interest and certain marine protected areas.

However, Greek law in reference to underwater archaeological sites states that “following a certain procedure, such places can be characterised as underwater museums and guided diving can be offered, accompanied by specialised personnel”.

The prefecture of Thessaly in the north-west Aegean Sea has initiated this procedure to put together Greece’s first underwater museum, which the project manager expects to open in 2015.

The plan is to open to divers a number of ancient shipwrecks around the Sporades islands, with suitable measures in place to guarantee the protection of the monuments.