It’s no small undertaking to explore Titanic’s sister-ship, the WW1 hospital vessel Britannic, which lies deep off Greece. A recent expedition with wreck preservation as its main aim took place in May, so how were the many pitfalls overcome?

Organizer ALEXANDER SOTIROU should know – photos by GEORGE RIGOUTSOS and JOACHIM BLOMME.

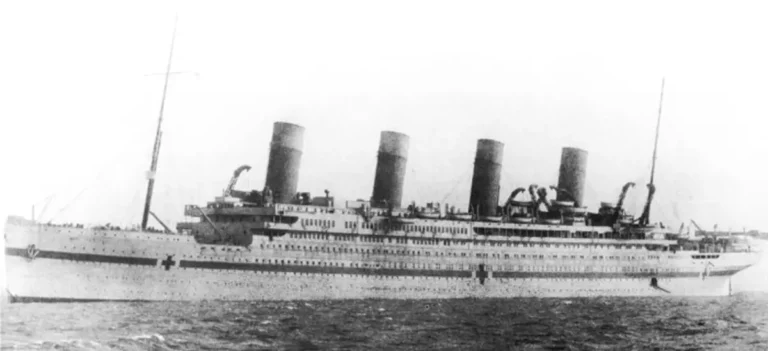

ONE OF THE WORLD’S BIGGER SHIPWRECKS, located in warm, clear water at a depth that has kept it relatively safe from environmental and human interference, HMHS Britannic is high on the list of sites any ambitious technical diver might wish to visit.

The idea for a 2012 expedition came from Belgian technical-diving instructor-trainer Paul Lijnen. As

I had been one of the divers on the first Britannic expedition in 1997, I had a good idea of the logistics involved in such a venture.

It seems like yesterday when British technical diver Kevin Gurr first raised the idea of diving the Titanic’s sister-ship. He was teaching my Trimix Diver course in Cornwall at the time.

The history of HMHS Britannic was less well-known then, and the only divers ever to have visited the wreck, deep in the Mediterranean off Greece, had been Jacques-Yves Cousteau and his team in the late 1970s.

On Kevin’s next trip to Greece, an attempt was made to pinpoint the wreck’s position. A local fisherman indicated a mark almost four nautical miles off the coast of Kea.

Robert Ballard had visited the Britannic on a US nuclear submarine in 1995, and had given the Greek authorities a position very close to this. Cousteau had reported the wreck to be further away.

The first dive on Britannic was off a RIB. Kevin Gurr, Kirk Kavalaris and I were extremely lucky that day.

The ship that we could hear approaching so loudly missed us…

IN NOVEMBER 1997 the first exploratory technical-diving project on HMHS Britannic lasted almost a month. It was much more than a virgin wreck that we were exploring. Diving on trimix beyond 100m was less common then. But the expedition was a success, and paved the way for more to follow.

Project Britannic 2012 has a more scientific character, its objective being to study how the wreck interacts with the environment.

RMS Titanic sank only a few years before her sister-ship, and everybody agrees that Titanic is in bad shape and deteriorating rapidly. Specific characteristics of a wreck’s environment are known to play an important role in its preservation.

Scientists from the National Oceanography Centre of Southampton (NOC) and the National & Kapodestrian University of Athens (UOA) volunteered to support the Titanic project with valuable scientific equipment and guidance.

Dr Thanos Gkritzalis specialises in water-sampling and analysis, using equipment he has developed for NOC, and Dr Vassilis Roussis of UOA is an expert in extracting and analysing substances from marine organisms that could have potential applications in pharmacology.

The diving team was put together, well-trained, equipped and experienced. They and the support group had to have the right attitude, and be willing to dive the plan.

HMHS Britannic is protected under specific Greek laws, and UNESCO guidelines that allow visits only if licensed by the Ministry of Culture.

The fixed licence dates leave no flexibility if plans have to be changed, so all logistics had to be arranged in detail, well in advance.

The expedition base chosen was Kea port, only 3.8 miles from the wreck. Paul Lijnen’s team of Belgian (and one Swiss) divers and the rest of the group were hosted aboard 15m sailing catamaran Athos and in the Karthea hotel.

With all the restaurants and cafes around the port, there was potential for the 10-day expedition period to seem like a real Greek-island holiday.

Rebreathers and bail-out cylinders were loaded aboard the 13m dive-boat Poseidon. The 50-litre gas cylinders were already stowed. Our aim was to keep equipment-carrying to a minimum.

On our first diving day, a site just outside the port was chosen. We planned a 20m wall dive to check equipment and acclimatise ourselves. The weather was fairly good, the wind mild, water temperature 20°C and visibility more than 30m.

The divers were all using electronically controlled closed-circuit rebreathers – Inspirations, Sentinels, Ouroboros and Auroras. These had been prepared for diving before being loaded in a van in Belgium to drive to Greece.

TEST DIVES ARE ALWAYS HELPFUL. One rebreather battery thought to be fully charged turned out to be almost flat, and an oxygen cell on another unit gave awkward readings.

Next day Dr Roussis and his UOA associates and the Ministry of Culture representative arrived. The official had to observe all diving on Britannic. Neither penetration nor any damage would be allowed.

On our second 20m test dive, the expedition ROV was dropped from Athos to observe the team. A rescue scenario was practised, with the diver “victim” brought up to the safety RIB, the first stage of a predetermined evacuation plan to the Naval Hospital of Athens.

A vehicle would be positioned on the nearby mainland coast.

The following morning, the team excitedly boarded the boats and set off on the short trip north-west. Poseidon’s echo-sounder was reading a stable 116m on the sandy bottom when suddenly the depth rose to 86m.

HMHS Britannic lies on its starboard side, bow facing south. After nearly an hour of careful GPS mapping, a shotline was dropped close to where the team calculated the bridge to be – 37 42.381N, 24 16.860E.

Allowing for possible drifting, the position was checked repeatedly as the divers kitted up. Current is usually strong in the area.

Part of the scientific work that day was to position Dr Gritzalis’s water-sampler on the wreck. Almost as big as a 7-litre sidemount cylinder, and slightly negatively buoyant, this was easy enough for a diver to carry to the bottom.

The device would take continuous water samples from the wreck throughout the expedition.

A miniature digital temperature-logger would also be used, and the samples later analysed to see how the wreck affected the water.

Two four-man teams were to be deployed with a 10-minute interval.

The plan was for a maximum depth of 95m, bottom time of no longer than 15 minutes and almost two hours’ decompression. Any additional deco stops indicated by the divers’ computers would also be conducted.

Trimix 7/65 was the CCR diluent. The PO2 was set to 1.2 bar until 6m, where everybody had to switch to 1.4 bar. Each diver would carry a trimix 10/65 bail-out cylinder, and within the diving team two divers would carry trimix 27/40 and the other two trimix 50/10.

The bail-out scenario would require the last part of a safe decompression to be conducted at the deco station, where nitrox 80 was located. In case of an SMB ascent away from the shotline, a standby diver would be carrying trimix 50/10 and nitrox 80.

BY THE TIME ALL DIVERS were back up shallower than 9m, on the three-level deco station, the wind had picked up to force 5. The real wind limit from any direction for Britannic dives is 3.

Stronger winds produce waves high enough to make climbing into the boat difficult, and decompression becomes uncomfortable as the station moves up and down.

The divers disconnected the deco station from the shotline and started drifting with the current. Passing ships, warned of diving activities on the wreck position, had been advised to keep at least a nautical mile clear.

The Athos crew was constantly checking on the radar the course of the huge commercial ships that cross the channel. They could gradually push them wide by moving into their way while they were still far off.

The fast 7m RIB had to approach smaller boats and explain the problem.

The divers had an idea of what was happening above them, but they could hear the motors, and feel in their stomachs the massive vessels’ vibrations.

At the predetermined ascent time, the first two divers reached the surface. Ascending in pairs at five-minute intervals made collection easier.

The RIB would take the sidemounts and Poseidon would approach for the divers to climb up. The sea state at the time was really bad, so they had to be carefully supported once on deck.

As a final precaution, they were given plenty of drinking water and 100% O2 for 20 minutes via a long hose system already installed on a 50-litre cylinder.

Heading back to the port, the expedition physician had a difficult time checking the excited divers’ condition.

“Standing on the platform of the boat waiting for the go sign, I was nervous,” said Paul Lijnen, the dive leader, describing his first visit on the Britannic.

“I have known the members of my dive team for many years – most of them are students of mine. All procedures had been practiced again and again, all equipment double-checked, but we knew the dive wouldn’t be an easy one.”

“Shortly after leaving the surface, descending into the warm, clear sea, I was completely calm. I kept my eyes on depth and PO2 indications. My team-mates were behind me.”

“The descent seemed to last for ages. Literally out of the blue, the grey silhouette of one of the world’s most magnificent liners appeared beneath me at 65m. The dive-line had been dropped very close to the open deck, a few metres behind the bridge. I could clearly see the explosion point and part of the bow. Wow, this is massive, I thought!”

Post-dive equipment care and next-day preparations didn’t take long. Trimix 7/65, already mixed in 50-litre cylinders, and oxygen were used to top off the rebreather cylinders via a gas-driven booster pump aboard Poseidon.

The two HP compressors on Athos would be used to fill drysuit inflation tanks and the cylinders that ran the booster.

We were able to discover more of inland Kea the next morning, while the wind was really strong. Ioulida, the main town, was only 15 minutes’ drive away.

The team discussed plans for a municipal multimedia room in the port of Kea dedicated to HMHS Britannic, using videos and stills from the expedition.

Very strong winds and heavy rain kept the boats docked again the next day.

A cold front had descended from the north, and team morale was low.

LATE THE NEXT MORNING, the rain stopped. The most optimistic weather forecast predicted the wind force to drop to 3 during the afternoon, but preparations for diving started anyway.

The shotline position was checked with the RIB. Perhaps the fact that Athos skipper Apostolos Roditis had gone on buying fish from the local fishermen for the last three days helped in keeping the red buoy in place.

By noon there were clear signs of improving weather, so a short afternoon dive was planned, with total runtime no longer than 90 minutes.

The second dive on Britannic was conducted close to the shotline. Both teams collected marine organism samples for Dr Roussis.

Organisms that grow on shipwrecks differ from those that grow elsewhere, and the samples would be analysed in UOA laboratories and compared with those Dr Roussis collected from Kea reefs on project days.

Over the following days the sea calmed down completely. Two more dives produced even more marine organism samples, including sediment from the seabed beside the wreck.

The four telemotors on the bridge were filmed in Blue-Ray quality, as was the complete bow area, including the cranes and mast.

On the fourth and last dive, the water sampler and shotline were collected.

Modern equipment and training have made dives to beyond 100m seem easier than they once were. The perfect vis and light conditions of the Greek Aegean Sea, combined with the relatively warm water, are also on the divers’ side.

But complicated deco procedures, strong currents, heavy shipping traffic, sudden weather changes and bureaucratic and logistical difficulties mean that diving HMHS Britannic will always be an expedition rather than just a diving trip.